Weierstrass substitution

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Calculus |

|---|

In integral calculus, the Weierstrass substitution or tangent half-angle substitution is a change of variables used for evaluating integrals, which converts a rational function of trigonometric functions of into an ordinary rational function of by setting .[1][2] This is the one-dimensional stereographic projection of the circle onto the line. The general[3] transformation formula is:

It is named after Karl Weierstrass (1815–1897),[4][5][6] though it can be found in a book by Leonhard Euler from 1768.[7] Michael Spivak wrote that this method was the "sneakiest substitution" in the world.[8]

The substitution

Introducing a new variable sines and cosines can be expressed as rational functions of t, and dx can be expressed as the product of dt and a rational function of t, as follows:

Derivation of the formulas

Using the double-angle formulas, introducing denominators equal to one thanks to Pythagorean theorem, and then dividing numerators and denominators by one gets

Finally, since , the differentiation rules imply

and thus

Examples

First example: the cosecant integral

We can confirm the above result using a standard method of evaluating the cosecant integral by multiplying the numerator and denominator by and performing the following substitutions to the resulting expression: and . This substitution can be obtained from the difference of the derivatives of cosecant and cotangent, which have cosecant as a common factor.

These two answers are the same because

The secant integral may be evaluated in a similar manner.

Second example: a definite integral

In the first line, one does not simply substitute for both limits of integration. The singularity (in this case, a vertical asymptote) of at must be taken into account. Alternatively, first evaluate the indefinite integral then apply the boundary values. By symmetry, which is the same as the previous answer.

Third example: both sine and cosine

if

Geometry

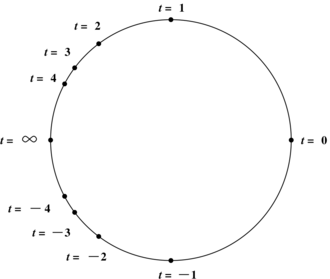

As x varies, the point (cos x, sin x) winds repeatedly around the unit circle centered at (0, 0). The point

goes only once around the circle as t goes from −∞ to +∞, and never reaches the point (−1, 0), which is approached as a limit as t approaches ±∞. As t goes from −∞ to −1, the point determined by t goes through the part of the circle in the third quadrant, from (−1, 0) to (0, −1). As t goes from −1 to 0, the point follows the part of the circle in the fourth quadrant from (0, −1) to (1, 0). As t goes from 0 to 1, the point follows the part of the circle in the first quadrant from (1, 0) to (0, 1). Finally, as t goes from 1 to +∞, the point follows the part of the circle in the second quadrant from (0, 1) to (−1, 0).

Here is another geometric point of view. Draw the unit circle, and let P be the point (−1, 0). A line through P (except the vertical line) is determined by its slope. Furthermore, each of the lines (except the vertical line) intersects the unit circle in exactly two points, one of which is P. This determines a function from points on the unit circle to slopes. The trigonometric functions determine a function from angles to points on the unit circle, and by combining these two functions we have a function from angles to slopes.

Gallery

Hyperbolic functions

As with other properties shared between the trigonometric functions and the hyperbolic functions, it is possible to use hyperbolic identities to construct a similar form of the substitution, :

Geometrically, this change of variables is a one-dimensional analog of the Poincaré disk projection.

See also

- Rational curve

- Stereographic projection

- Tangent half-angle formula

- Trigonometric substitution

- Euler substitution

Further reading

- Edwards, Joseph (1921). "Chapter VI". A Treatise on the Integral Calculus with Applications, Examples, and Problems. London: Macmillan and Co, Ltd.. https://archive.org/details/treatiseonintegr01edwauoft/mode/2up.

Notes and references

- ↑ Stewart, James (2012). Calculus: Early Transcendentals (7th ed.). Belmont, CA, USA: Cengage Learning. pp. 493. ISBN 978-0-538-49790-9. https://archive.org/details/singlevariableca00stew_704.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Weierstrass Substitution." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- ↑ Other trigonometric functions can be written in terms of sine and cosine.

- ↑ Gerald L. Bradley and Karl J. Smith, Calculus, Prentice Hall, 1995, pages 462, 465, 466

- ↑ Christof Teuscher, Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker, Springer, 2004, pages 105–6

- ↑ James Stewart, Calculus: Early Transcendentals, Brooks/Cole, Apr 1, 1991, page 436

- ↑ Euler, Leonard (1768). "Institutiionum calculi integralis volumen primum. E342, Caput V, paragraph 261". Mathematical Association of America (MAA). http://eulerarchive.maa.org/docs/originals/E342sec1ch5.pdf.

- ↑ Michael Spivak, Calculus, Cambridge University Press , 2006, pages 382–383.

External links